In 1852, J. W. Mackay discovered coal in the bush on VanIsle. But there were other places on VanIsle with coal. So, where was MacKay?

Almost 200 years later, it’s now the hipster recreation village and self-proclaimed Legendary Cumberland.

Coal had already been discovered near Nanaimo. Mackay figured more seams might exist further up Island. And he was right.

But his early prospecting success didn’t immediately turn into big profits. When more prospectors followed Mackay, they formed the Union Company. But they didn’t have much working capital. Even with the coal right there, they struggled.

Enter the shrewd Robert Dunsmuir, who recognized a winner. He got involved and formed the Union Colliery Company of British Columbia. That’s when the Island coal boom took off for real.

By the 1880s, miners were building houses in a settlement then called Union. The name wasn’t exactly inspiring.

Folks built churches, and they built bars. In 1898, Union was incorporated and renamed Cumberland, after the English County.

It was an appropriate name change. Cumberland, in the northwest of England, has a long history of coal mining dating back to 1560.

In the early 1700s, a local mining family started sinking shafts on England’s Cumberland coast to work coal seams beneath the seafloor. English miners immigrated to Canada. Some brought the skills they learned in the damp Cumberland mines of the old country.

Those skills worked well in Dunsmuir’s Vancouver Island mines.

But they were dangerous mines. The air inside them was full of methane and carbon dioxide. Dunsmuir knew it. So did many European coal miners who refused to go underground.

So Dunsmuir’s company started recruiting Asian miners. Many of these folks were from impoverished villages in China and Japan. He paid their fares and head tax and then took these costs out of their wages.

That was indeed a dick move. It left the workers indebted and at the mercy of the company for years. To add insult to injury, he paid Asians half what their fellow Caucasian miners earned.

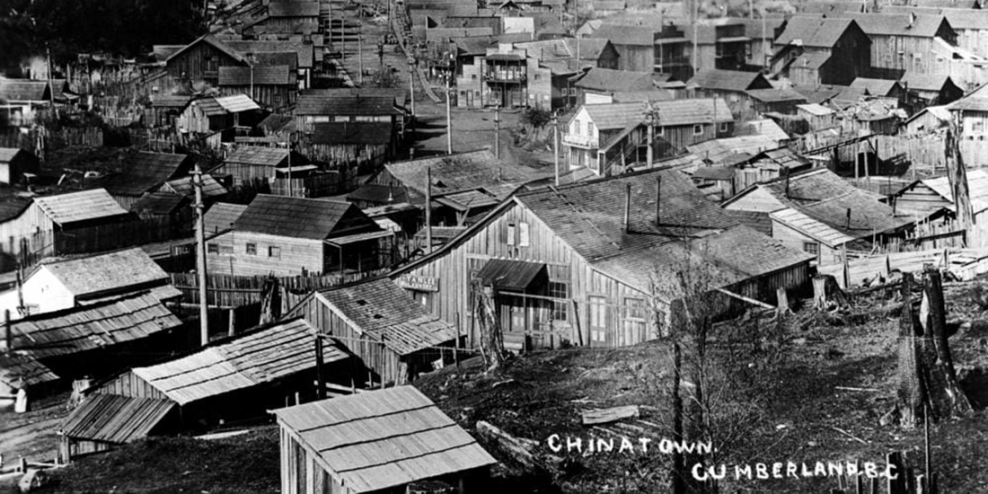

Groups of poorly paid Chinese and Japanese miners built their own thriving neighbourhoods on the only land available to them: the bogs and swamps on the edges of Cumberland. They grew market gardens and built shops. But the dangers of mining and the ballooning fortunes of Dunsmuir hung over the entire community.

Then, on Feb 15th, 1901, there was a massive underground explosion at No. 6 mine. Do you know Number Six Mine Park? It’s so peaceful. It’s right in downtown Cumberland. You’d never know it was the site of a disaster.

And it was a preventable disaster. It killed 64 people, including two 17-year-old boys. Roughly 2/3rds of the dead were Chinese and Japanese mine workers.

Tragedies like this one in Cumberland sparked a labour movement that caught fire across Canada.

Over the years, more than 100 Asian miners lost their lives in the Cumberland coal mines. So when people talk about “Legendary Cumberland,” there’s more to the story than craft beer, mountain bikes, and music festivals.

And there’s even more to the story than the town’s English namesake.

There are also the Asian miners who fought back against terrible pay and worse conditions. The labour movement they sparked made things better for workers for decades.