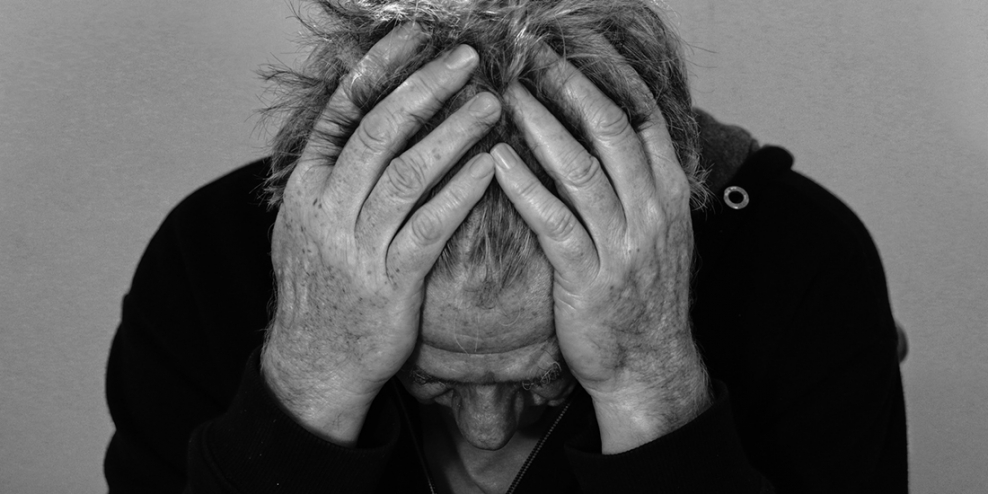

Last year, the Alberni-Clayoquot Health Region had the highest rate of deaths from toxic drugs on VanIsle.

But we still don’t have a detox centre. There’s the overdose prevention site and the sobering centre, and they do important work. But they are only part of the story.

Mariah Charleson is the vice president of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council (NTC). The NTC is pushing for a detox facility and rapid-access addiction clinic. “There’s not enough resources for people who need help right now,” said Charleson told Ha-Shilth-Sa.

The FNHA and Island Health found half a million dollars to fund four to six beds for folks going through withdrawal. But this is barely a drop in the bucket.

“These are low-barrier-based beds, it’s not a detox centre,” said Charleson. “We can’t accept this as a resolution, we need to keep pushing for what we’re asking for.”

Former mayor John Douglas thinks along the same lines. He works on special projects with the Port Alberni Shelter Society. “We’ve done lots of work keeping people alive,” he told the Globe and Mail, “but not much helping them recover.”

The toxic drug crisis affects Indigenous people more than other folks. Of the people who died from toxic drugs last year, 15 percent of them were Indigenous. But Indigenous folks make up less than six percent of BC’s population.

More First Nations leaders on Vanisle have echoed Charleson’s call. They’re calling for a stabilization centre for people dealing with addiction.

And that kind of detox centre is just the first step in the journey. What happens to folks who get through detox and rehab if there’s nowhere to go after that?

That’s where Therapeutic Recovery Communities (TRC) come in. These communities help a person recover long-term. They provide a place to live, friends, support, and job skills training.

Wes Hewitt is the executive director of the Port Alberni Shelter Society. They’re running a community like this on their Shelter Farm about 10 km outside of Port Alberni. For now, the program has beds for six women who are in long-term recovery.

“Within the recovery model there is education, as in skills and empowering the individual so that when it’s time that they graduate from the program they have a job, something that can pay the bills and they have a home to go to,” he told Ha-Shilth-Sa.

“They’re not just dumped on the street or dumped back into the same situation that they were in before.”

Guy Langois is the farm manager at Shelter Farm. He told Nancy Wilmot of Up Front that clients are referred to the farm through Island Health. The women in the program are recovering from trauma and addictions.

“We offer up to two and a half years for people to work there, learn skills, they’ll be engaged at the farm,” he told Up Front. Women in the program help grow food on the farm, which brings in revenue to make the program possible.

Two and a half years might seem like a long time. But places like Italy have run centres like these for decades. They’ve proven that the sense of connection and purpose folks get in the centres are great for staying clean in the long term.

The Tiny Homes Project shares a lot in common with TRCs. It’s a long-term housing community that focuses on Indigenous culture and building connections to help residents get back on their feet.

While these programs are a great start, WestIsle will need more services to support folks who want to get clean and stay that way.

You can help us get those services. The province has a survey that will run until August 5th, 2022. The survey asks British Columbians what they want to see happen to support folks who are suffering in the toxic drug crisis.